|

| Rebel works in front of Atlanta and a scene of ruined depot in Charleston (Fleischer's Auctions) |

Keith F.

Davis recalls visiting a New York City gallery in 1977. On display was the full

set of 61 images from George N. Barnard’s “Photographic Views of Sherman’s

Campaign,” a volume that documents the general’s game-changing conquest of

Atlanta, Georgia and South Carolina.

What Davis

saw set him off on a journey of discovery.

“They were quiet, without obvious action, and

many were primarily ‘landscape’ photographs,” he says. “They were more about

memory and meditation than ‘action’. All in all, I felt puzzled and challenged

by this work, because it didn’t easily conform to what I had expected to see.”

Davis felt

challenged by the photographs and began a deep study of them and the man,

eventually leading to a book on the subject. Today, Davis is the leading

authority on Barnard, who ranks among the top echelon of Civil War

photographers – Gardner, O’Sullivan, Cook, Rees, Reekie, Gibson and Brady.

“None of them surpassed Barnard in terms of

technical or creative skill,” says Davis (photo, left), a photography curator, author and

collector. “It’s hard to say that any one of them was 'the best' but Barnard

was second to none.”

A rare copy

of “Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign,” thought to belong to Maj. Gen.

William T. Sherman and signed in 1886 by his son Philemon, will be up for bid during

Fleischer’s Auctions’ May 14-15 sale in Columbus, Ohio. (Sherman died in 1891.)

The Barnard album is among the top Sherman-related items in the auction. Notable items from

the family, many of whom live in western Pennsylvania, include the general’s

copy of the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, with his annotations, a trunk and saber

used early in the Civil War, shoulder straps with rank insignia, photographs of Sherman and his daughter Minnie and a family Bible.

“These items … may represent the most important sale of

Civil War artifacts in recent memory,” company president Adam Fleischer said in a statement. “It is my sincere hope that through this process, these items will

find themselves in the hands of individuals or institutions who will preserve

them, ensuring that General Sherman's story endures and continues to enrich our

collective understanding of such a pivotal era in American history."

The auction includes relics of the

Revolutionary War, the African-American experience (including a broadside used

to recruit soldiers during the Civil War) and the Wild West.

Steve Davis,

author of several books on the Atlanta Campaign, including “What theYankees Did to Us: Sherman’s Bombardment and Wrecking of Atlanta,” told the

Picket that Union Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs took

interest in Barnard’s work and asked him to photograph Nashville. The

photographer also traveled to Knoxville and Chattanooga, Tenn.Barnard, a pioneer in the field, served as the official photographer of the

Military Division of the Mississippi, led by Sherman.

On July 28, 1864,

Capt. Orlando Poe, Sherman's chief engineer, wired Barnard, "Hold yourself

in readiness to take the field if telegraphed to that effect." A few days

after Atlanta fell, on September 4, Poe telegraphed Barnard to join him.

“A week or so

later -- we're unsure of the date -- Barnard arrived in Atlanta and was soon

taking pictures of the city, its surrounding fortifications and the

battlefields of July,” said Steve Davis.

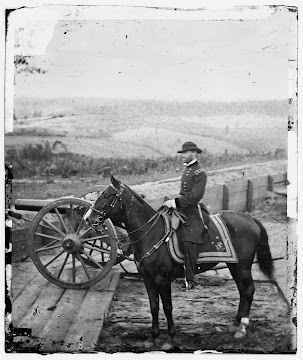

Interestingly,

a famous Barnard photograph of Sherman astride a horse (above, Library of Congress) is not included in the

book.

On October 1,

1864, Sherman wrote his wife Ellen, "I sent you a few days ago some

photographs, one of which Duke was very fine. He stood like a gentleman for his

portrait, and I like it better than any I ever had taken." Sherman wore

formal attire for the camera session – sash, sword and all.

“Barnard's

famous picture of him sitting on Duke in a Rebel fort west of the city is

iconic,” says Steve Davis (photo, left).

The volume -- featuring 10 x 13 inches images

-- includes scenes of the occupation of Nashville, battles around

Chattanooga and Lookout Mountain, the Atlanta Campaign, Savannah, Ga., and South

Carolina. In May 1866, Barnard traced

the route of Sherman's North Georgia campaign, taking pictures at Resaca and

elsewhere.

When Barnard arrived in Atlanta he took more, including his famous views

of the downtown area that had been burned by the Federals before they left on

November 15-16, 1864, says Steve Davis.) Many copies of the volume are held by

museums and other institutions.

Charlie Crawford, president emeritus of the Georgia Battlefields Association, said Barnard's contract with the Army called for him to principally take photos of fortifications, and he took many.

“We're lucky that he had time to take photos of the Ponder house, car shed, etc.” says Crawford, who has led many tours of areas that were key in Civil War Atlanta.

“His 1866 photos destroy the myth that all of Atlanta was burned to the ground, since many of the same buildings appear in his 1864 photos,” says Crawford. “As Steve Davis writes in his book, destruction was concentrated along the rail lines, where many of the factories and warehouses were located.”

|

| Remarkable clouds above railroad destruction in Atlanta (Fleischer's Auctions) |

The Picket asked Keith F. Davis about Barnard’s techniques, artistry and legacy. He responded by email. The responses have been

edited.

Q. What is the significance of this collection

of his works? Apparently, relatively few of the volumes were made.

A. In its ambition,

seriousness and artistic quality, Barnard’s album is one of the greatest

photographic works in American history. Of course, it is one of two comparable

productions of the immediate post-Civil War period. Alexander Gardner’s

“Sketchbook,” with 100 original albumen prints, was issued in early 1866.

Barnard’s “Sherman’s Campaign,” with 61 original prints was completed in the

fall of 1866. Both were marketed to a wealthy and elite community of buyers -- largely

former Union officers -- and sold by prospectus. Neither of these expensive

works was ever intended for anything like “general” or “popular” sale. They

were rare, deluxe collectibles, not “books” in any traditional sense. These are

very different albums -- they cover different aspects of the war, with no

overlap at all, and they cover their respective territories in distinct ways.

Barnard’s album was produced in an original

edition of 100 to 150 copies, and priced at $100. Not very many have survived

today, intact and in good condition. Some were lost or damaged over the years,

and since the 1970s, a significant number have been cut up so that prints could

be sold individually.

Q. Why did you choose to write about Barnard?

What is his contribution to wartime journalism?

A. I became fascinated by

Barnard (photo right by Brady, National Portrait Gallery) in 1977, when I was studying with (curator and art historian) Beaumont

Newhall, getting my MA at the University of New Mexico. Dover had just issued a

paperback reprint of Barnard’s album, with an introduction by Beaumont. I

remember him talking about his work in class. In the summer of 1977, I saw an

exhibition of a complete (disbound) “Sherman’s Campaign” album at a gallery in

New York City -- perhaps the first time the full set of pictures had ever been

displayed. I was struck by the quality of Barnard’s contact prints (made from

12x15” wet-collodion negatives) and, most importantly, by the “weirdness” of

the whole set. I thought I knew something about the history of war photography,

but these pictures seemed distinctly different from whatever “tradition” I knew.

They were quiet, without obvious action, and many were primarily “landscape”

photographs. They were more about memory and meditation than “action.”

All in

all, I felt puzzled and challenged by this work, because it didn’t easily

conform to what I had expected to see. That triggered a deep fascination for

Barnard’s life and work. I ended up getting an NEH research fellowship for this

work in 1986, and published my book “George N. Barnard: Photographer of Sherman’s Campaign” in 1990, accompanied by a traveling exhibition in 1990-91.

I was completely fascinated by the challenge or “problem” of Barnard and in my

dozen or more years of intensive research, ended up greatly expanding what was

known about him.

My real understanding of 19th century American

photography in general certainly grew from, and around, this project. (Davis

also covered the topic in a Civil War chapter in "The Origins of American Photography: From Daguerreotype to Dry-Plate” below, 2007)

Barnard wasn’t primarily a “photojournalist.” A

number of his works were reproduced in the illustrated papers of the day, and

some stereographs were sold to a popular market. Primarily, however, he was

working as a civilian employee of the Union Army’s Engineering Department,

creating images that were primarily used for internal military use.

Of course,

these boundaries were fluid: Barnard was friends with Theodore Davis, a skilled

sketch artist and writer for “Harper’s Weekly”; he maintained connections to

the commercial firm of E. and H. T. Anthony, which marketed war images to the

general public; and, of course, he was a self-motivated entrepreneur who

conceived, created and marketed his album to the elite audience described

above.

Q. Can you speak to his technical and creative

skills?

A. Barnard was extremely

accomplished in both technical and aesthetic terms. He had been a

daguerreotypist for more than a decade, then had worked for the Anthonys in

New York City, and for Alexander Gardner in Washington, D.C. So, he was hugely

experienced. In the field, he preferred his 12x15” view camera, making

negatives of that size, and final prints that trimmed down to about 11x14”.

And, as we know, he was an American pioneer in printing-in clouds from a second

negative -- there are numerous instances of this in his “Sherman’s Campaign”

album.

This technical labor was clearly not needed for strictly “documentary”

purposes. Rather, he did it for aesthetic reasons, to make images that were

both informative and artistic. And that gets to the key nature of his album.

Rather than a “simple” work of documentation, it is instead something more

complicated: a factual collection of places/views that combines memory, poetry

and artistry in order to evoke something about the war’s justification, its

horrific costs, and its relation to American character and values. There is a

poetic and essentially literary aspect here that makes this album unusual and

special.

|

| Barnard's eerie image of McPherson's death site includes horse skull (Fleischer's Auctions) |

In part, the nature of the album is a result of

when and how the images were made. Barnard held a number of his original

negatives from 1864. Once he decided to proceed with the album, he made a

re-photographic trip back over the same ground in the spring of 1866 -- to

record sites he had not photographed in 1864 and, in general, to enlarge his

visual record of the ground that Sherman had covered.

He only printed-in skies

in 1866; earlier prints from the same images exist, and they do not have the

printed-in skies. Thus, the album blurs two distinct time frames: the 1864

views with troops visible, defensive works in optimum condition, etc; the 1866

prints of some of those negatives, now with cloudscapes; and the new 1866

views, without any evidence of military presence, of battlefields, defensive

works, etc., as they stood a year and a half after the events of the war.

Q. Do you know whether he knew Sherman, and if

so, to what extent? I understand Barnard worked for the Army and came to

Atlanta soon after the surrender.

|

| Barnard used clouds to bring drama to a scene, such as at an Atlanta fort (Fleischer's Auctions) |

A. Barnard certainly knew

Sherman, and vice versa, but they were not close friends or associates -- the

social gap between general and staff photographer was just too great for that.

But we know that Sherman supported Barnard’s project when he heard about it,

and wrote a warm letter of endorsement. Barnard was aided in all of this by his

superior, Orlando M. Poe, who was Sherman’s chief engineer. Poe supported

Barnard consistently: he allowed Barnard to keep some of his wartime negatives

for his own postwar use, and in 1866 he contacted Sherman and other generals to

promote (and solicit buyers for) Barnard’s album.

Q. Do you have any anecdotes about his time in

Atlanta and in the Carolina?

A. Barnard was a distinctly

intelligent, ethical and upright man. He supported the Union cause

wholeheartedly and was an abolitionist from the start. There is also, however,

clear evidence that the death and devastation of the war shocked him to the

core. He accompanied Sherman’s troops on the March to the Sea but – notably -- made

not a single photograph along the way. They were moving quickly, sure, but if

he had really wanted to make images, he could have found a way to do it. This

says something to me about his dismay at what he saw Union troops doing along the

way.

|

| Capitol in Nashville and view from Lookout Mountain, click to enlarge (Fleischer's Auctions) |

Q. Which of the photographs in the book particularly stand out?

A. In terms

of my favorite individual images, that’s a bit difficult, since I love the

totality of the album, but I have always been particularly fond of:

-- The

Capitol, Nashville

-- Chattanooga

Valley from Lookout Mountain

-- Scene of

Gen McPherson’s Death

-- Rebel

Works in Front of Atlanta No. 3

-- Destruction

of Hood’s Ordnance Train

-- Ruins of

the RR Depot, Charleston